The Best Workout Clothes for Women to Wear on Repeat in 2023

Oh hello, new leggings.

By Talia Abbas

Source Posted on February 21, 2023

Gym clothes have come a long way from their humble T-shirt-meets-spandex-bottoms heyday—and the best workout clothes for women today have to meet a variety of fits and needs before they can claim a prime spot in our rotation. Between lounging and working out, we ask a lot from our athleisure (not to mention our wardrobe essentials in general), so it’s essential to invest in workhorse pieces that can go anywhere, do anything, and still make you feel like your best self.

Stylish options to flex your fashion sense are obviously a must, but most of us also want workout leggings and sports bras that are comfy, functional, and supportive—especially if these are pieces you’re slipping into on a bleary-eyed morning (amirite?). Tons of brands know this, and the active and loungewear space is thriving with options right now across a range of price points and sizes.

To help you build the ultimate workout wardrobe for doing all the things, we’ve curated a list of MVP-worthy activewear brands—many of which you probably already know, love, and have shopped before. From sportswear icons like Nike to sustainable brands like Girlfriend Collective, below you’ll find a comprehensive guide to stocking up on the best workout clothes for women in 2023.

Colorfulkoala

Amazon shoppers can’t get enough of Colorfulkoala’s workout gear—and neither can TikTokers who claim the leggings are “so cute,” “so soft,” and “almost an exact dupe for Lululemon’s buttery Align leggings.” The brand doesn’t just make leggings; you can also find comfy and smoothing workout tanks, sports bras, and bike shorts.

Lululemon

Lululemon doesn’t play around with its workout gear, but you already knew that. The brand’s claim to fame is its supersoft Align leggings, which wear like second skin and are ubiquitous at workout studios, supermarket checkout lines, and cute local brunch spots alike. (Sizes run from 0 to 20.) Going for a full look? Check out its vast collection of sports bras, which range from low to medium support to high-impact—and come in styles like high-neck, longline, and racerback. (Pro tip: Keep your eyes peeled on its We Made Too Much section to score seasonal hues at a fraction of the original price.)

Alo Yoga

Alo has a loyal roster of celeb fans (Kendall Jenner! Jennifer Lopez! Kaia Gerber!) and for good reason: The brand designs workout clothes that fit like a dream, whether you’re doing a vinyasa flow in your kitchen or taking your furry baby for a stroll around the block. The brand has coined a number of technical performance fabrics like Airlift and Alosoft since its early-aughts debut, and you can find simple silhouettes as well as more on-trend styles in its lineup—think pleated tennis skirts, asymmetric sports bras, sleek long-sleeve bodysuits, and its best-selling leggings.

Girlfriend Collective

Using recycled plastic water bottles and fishing nets, Girlfriend Collective designs affordable, size-inclusive athleisure in an Instagram-friendly palette of colors like lilac, sage, and auburn. Top and bottom sizes start at XXS and go up to 6XL, with short (23.75″) and long inseams (28.5″) available for its top-rated leggings and comfortable unitards.

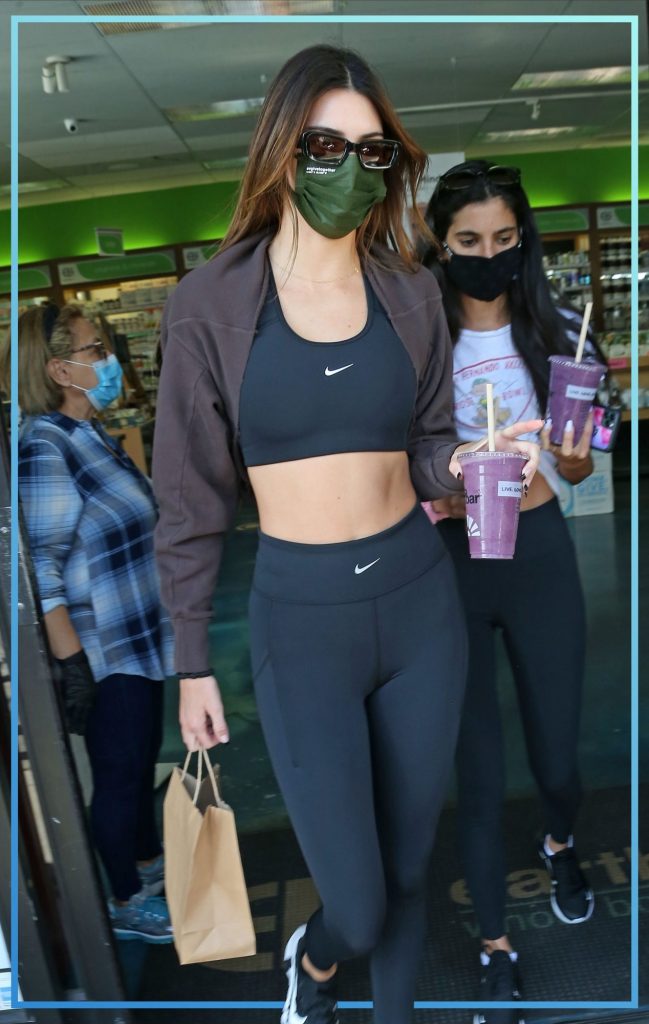

Nike

Workout sneakers aside, Nike makes the gear of choice for pro athletes and, well, just about everyone else. The heritage brand has a near-infinite range of leggings, hoodies, running shorts, and workout tanks for straight and plus sizes—and keeps things fresh with coveted designer collaborations that blend high-performance fabrics with fashion-forward silhouettes.

Adidas

Adidas and its iconic three stripes need no introduction. The activewear giant has been leading the charge in sustainable fabric innovation for years now, with the main mission of ending plastic waste. (It has an ongoing partnership with Parley for the Oceans to use recycled plastic debris and certified fabrics in its designs, and half of its collections are made of recycled polyester.) Adidas also has a long-standing collaboration with Stella McCartney, a pioneer in sustainable women’s wear design.

Outdoor Voices

Outdoor Voices kicked the whole athleisure movement into high gear when it debuted its pastel color-block leggings in 2014, and the brand remains a go-to for exercise clothing that’s just downright fun to wear. Cute crop tops? A mainstay. Skorts? Those too. How about a dress to dance in? As if you’d want to wear anything else.

Zella

Nordstrom carries a mix of legacy workout brands—from Sweaty Betty to Nike—that you’re probably already familiar with, but don’t sleep on its in-house label, Zella. The Nordstrom-owned brand sells everything from sweat-wicking cover-ups to nap-ready sweatpants, with shoppers unanimously obsessed with its high-waist Live In leggings. The bestseller has more than 7,200 rave reviews on Nordstrom’s site (not to mention Glamour‘s own stamp of approval) and comes in a full-length and cropped version.

Beyond Yoga

Beyond Yoga has some of the best fabrics in the game, with Spacedye arguably being the star of the show. This one-of-a-kind fabric is stretchy yet supportive, and deliciously cool to the touch. You can find it on everything from cropped tanks to low-impact bras and maternity yoga pants (which tons of stylish women swear by during pregnancies, FYI).

All Access

Bandier’s in-house brand All Access has truly nailed the trifecta of durable, stylish, and versatile activewear. The buzzy label offers a tight-knit edit of leggings, bike shorts, and sports bras available in a rainbow palette of colors and lengths, from three-inch biker shorts to capris and high-waist options with pockets. Shop items separately, or snap up one of its kits to mix and match (and save a little coin while you’re at it).

Port de Bras

Port de Bras is a relative newcomer in the activewear space, but one you should definitely have on your radar. The ballet-inspired brand gained momentum in 2020 for its unique, high-fashion approach to performance wear, with founder Clarissa Egaña prioritizing the use of traceable, eco-friendly fabrics for her pieces.

Tory Sport

Function meets form at Tory Sport, which you can rely on for high-quality essentials that go beyond your everyday lounge and studio needs. The brand has plenty of adorable tennis sets, chic golf dresses, swimwear, and glamping gear to put a luxe spin on whatever activity you’re doing.

Set Active

Get ready to live in Set Active’s lounge and workout sets. The cool-girl brand serves up sculpting styles in snap-worthy hues like mint, espresso, and sage.

FP Movement

Free People’s sportswear-focused sister line has a vast selection of onesies, sports bras, and bike shorts that look as good as they feel. Also new for spring 2023? Swim (under the name FP Beach), so add them to the list of best swimwear brands, stat.

Athleta

You know Athleta, you love Athleta. Gap’s sister brand is a mainstay for workout gear that goes as hard as you do. Beyond the essentials, it also carries a ton of everyday styles—think down jackets, cozy wraps, and comfy travel pants.

Aritzia

Come for the Super Puff jackets and Melina leather trousers, stay for Tna’s plush hoodies and sweatpants that you’ll never want to take off. Also great here? It’s white T-shirts and tank tops for throwing over anything from jeans to leggings.

Vuori

Vuori has had a loyal following for years now, but only recently did the brand go mass thanks to TikTok virality. The brand’s sherpa jacket was a top seller in the health and wellness category in 2022, according to LTK, but we’ve always loved its adjustable drawstring leggings and joggers.

Splits59

From sleek turtleneck tops and buttery-soft bras to high-rise leggings and bike shorts, Splits59 makes some of the best low-to-medium impact sportswear, which is why we love it so much. Also noteworthy: Many leggings come in cropped versions so petites can feel represented too; the flared Raquel crop is a noted editor favorite.